Saving KendallBy Martha BayneThe kitchens on its Goose Island campus are stocked with state-of-the-art equipment and the halls are bustling with future chefs and restaurateurs. But not four years ago Kendall College was a sinking ship.

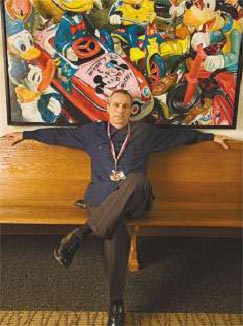

By 2002 the physical facility was deteriorating—the kitchens were crowded and sweltering, the equipment was showing its age, and Evanston's restrictive city bureaucracy made growth difficult. Reardon says the budget was deep in the red and a series of leadership upheavals—three presidents in the previous four years—had the board doing little besides convening search committees. Few members thought Kendall could invest any more in the culinary program, but they also believed that if it didn't the entire college was doomed. That fall after two years under interim leadership, the school hired its current president, Howard Tullman. An attorney, entrepreneur, and turnaround artist who freely admits he doesn't know a damn thing about cooking, Tullman had most recently been the CEO of a digital strategy and Internet design firm called Xceed; before that he'd run "Tunes.com, an online multimedia site sold to" eMusic.com in 2000 for around $170 million. Outside the business world he's probably best known as an avid art collector who's donated work from his extensive contemporary collection to Northwestern's Block Museum and the Milwaukee Museum of Art. In business and in life Tullman is a notorious detail hound, with so many fingers in so many pots it's hard to keep track of them all. He's been a lawyer and a horse breeder. He's produced a Broadway musical and written a (still unsold) screenplay. He's famous for 3 AM e-mails and a blunt, often profane management style. He's run 12 marathons and maintains an exhaustive Web site (tullman.com) chronicling his various other activities and enthusiasms. It includes an archive of his art holdings, a five-page resumé, articles on his business dealings, pictures of his large collection of Pez dispensers, an alphabetically organized section of sayings titled "Words of Wisdom," the syllabus for an entrepreneurship class he teaches at Northwestern's Kellogg School of Management, photos of himself and his wife, Judy, at the Clinton White House, and the text of the toast he gave at his daughter Jamie's wedding. Other than the Kellogg class, Tullman had no experience in education before he came to Kendall. As he's fond of saying, he was brought to Kendall "to save it, sell it, or shut it down," which is above all a business challenge. "The school had a great culinary school and a great reputation," he says, "and it was kind of trapped inside the body of this giant, unwieldy, unworkable institution that was trying to do a lot of different things and doing most of them fairly poorly. My interest was in whether you could extract what was valuable, in terms of what the school did well, and focus on those things. Then maybe you could save it." Tullman got approval from the board to fix the problem by any means necessary. Within two weeks he'd drawn up a 15-page memo outlining his priorities and the steps he was going to take to accomplish them. He added several former business associates to the administrative roster, including a new dean of students. He sat the faculty and staff down and explained just how strapped the college was for cash—at least a million in the hole and likely to close in as little as 90 days." Educating the faculty about the financial situation was very critical so they understood both the severity and the urgency of things," he says. "I don't know if they did. I don't know if they understood that they were quite close to being out of a job." The biggest change was yet to come. In May 2003 Tullman happened to drive by the shuttered Sara Lee R & D building on Halsted just north of Chicago Avenue. Within days he'd met with the owner of the Goose Island property and pitched its purchase—in his words, "the opportunity of a lifetime"—to the board. Over the next three weeks he brokered deals with Sara Lee and the owners of the six acres the facility sat on, got approval from the board, the city, and the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools to move the school, sold the Evanston campus for $10 million, and raised another $50 million to finance the renovation and move. Kendall's Riverworks campus was open for business by January 2005. "It was wild," says culinary school dean Christopher Koetke of the intervening year. "There was all the euphoria of a start-up company—the long days, the feeling of going somewhere you'd never been before. In any sort of business planning you always want to sort of look backward and try and understand things to forecast. But we changed so many things that all our forecasting models went out the window."

Koetke remembers spending an inordinate amount of energy putting out fires. "There were rumors," he says. "People were obviously worried and scared about ‘What all does this mean for me personally?'" He pauses. "The culinary world is sort of a special world. And culinary people do well with other culinary people. The fear is if you bring in someone who doesn't understand the culinary piece, you know, they get a little worried— like he's not going to understand what we're all about. Maybe he's not going to understand what we need to do in order to teach well." "You can't afford to provide a good education if you're not running a sensible economic institution," says Tullman. "I think a lot of them thought I wouldn't appreciate what went into teaching or how much of an art it was as opposed to a science." By the time the new campus opened the curriculum had also been revamped. Gone were things like athletics and Web Development classes. In their place were comprehensive bachelor's programs in culinary arts, hospitality management, and early childhood education, another Kendall staple, and associate's degree options in culinary and baking and pastry. (A business program was added to the mix this year.) Some students and staff lamented the loss of the cozy atmosphere and green space of the Evanston campus, but most saw the improvements as huge. "It's like going from driving a Hyundai to driving a Cadillac," says baking and pastry instructor Mark Kwasigroch. "Everything is state-of-the-art." The new teaching kitchens were outfitted with industry innovations like programmable ovens and rolling blast chillers, which are essentially reverse convection ovens that rapidly cool food by blowing cold air around at high speeds—important, says Koetke, given ever-more-stringent FDA regulations. Two demo kitchens double as TV studios used to produce both in-house teaching videos and instructional DVDs for various clients. The wine classroom is outfitted with a wall of one-way glass for use in focus groups. Two baking and pastry kitchens feature industrial strength mixers, dough cutters, and steam-injected ovens. The sugar and chocolate kitchen has cool granite countertops and ice cream machines. In the third floor garde-manger kitchen—dedicated to the creation of cold items like patés, terrines, and charcuterie – a hefty Enviropak smoker has replaced the jury-rigged Peking-duck oven students had used for years when learning how to cure sausage. A lot of the new gear came courtesy of another Tullman business decision – strategic partnerships with corporate benefactors, including Kraft, Sub-Zero and CookTek. A corporate presence is nothing new in the food world – the Culinary Institute of America's campus in Hyde Park, New York, is home to the Colavita Center for Italian Food and Wine, a freestanding, 18,000 square-foot facility modeled on a Tuscan palazzo and named fort he olive oil that funded it. But it's certainly new to Kendall. A $25 million cornerstone of the deal he brokered was a partnership with Laureate Education, an international for-profit consortium of both bricks-and-mortar and online universities (it used to go by the name Sylvan Learning Systems), Laureate has an option to buy Kendall outright, and Tullman expects they'll exercise it by the end of this year. If they do, Kendall will become a wholly owned subsidiary of Laureate, as are other career-specific schools like the online Walden University and the Switzerland-based Les Roches School of Hotel Management, with which Kendall is already developing is hospitality program. Laureate's investment doesn't affect Kendall's curriculum on any practical level, but its one manifestation of the increasingly global nature of the U.S. culinary and hospitality industry – an industry that, according to the National Restaurant Association, already employs 12.5 million Americans and is expected to add another 1.9 million jobs in the next 10 years. Some partners, though, are more hands-on. Kraft, for instance, regularly contracts out projects to its namesake research and development kitchen at Kendall, and BA students in the required R&D class present their final projects to a panel of Kraft executives. Even something as humble as the pastry kitchen's electromagnetic CookTek induction burners, reflect Kendall's new emphasis on what the suits call synergy. The students benefit from the state-of-the-art equipment because, in an industry ever more reliant on technology, it makes them competitive in the marketplace. (One student who started off in Evanston isn't completely sold on the concept, noting that there are benefits to learning on old equipment because, frankly, "that's what a lot of restaurants have.") Koetke says the industry benefits because "here you've got 500 culinary students – high quality students who are going to do things in the business. If I was a manufacturer I would want to get my best stuff in a place like this because – guess what? – they're going to learn to cook on that stuff and they're going to go out in the industry and when its their turn to buy stuff who are they going to think of?" Other changes are less visible but speak to Koetke's conviction that Kendall is in the business of training not just chefs but industry leaders. Culinary course work includes classes in management, accounting, marketing, and the political and legal issues of food. One of his pet innovations is the creation, with the Resource Center's Ken Dunn, of a comprehensive campus-wide composting program. Koetke has also led the charge to switch the oil in the school's 30 deep fryers from partially hydrogenated vegetable oil to a trans-fat free soybean oil called Asoyia, produced by an Iowa farmer's cooperative. "We made a decision to switch over to this oil because we want our students to think about this not as something static, but as something that's always changing," he says. "We want to be sort of on the forefront of what's going on because we want (the students) to think that way."

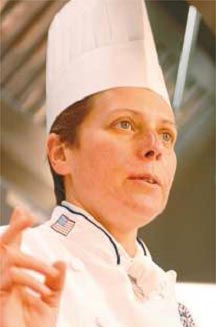

Once upon a time aspiring cooks apprenticed themselves to a master or started out as dishwashers and painstakingly climbed the ladder. But the industry has changed so much that it may no longer be enough to pick up the craft on the fly. Those 1.9 million new jobs aren't all going to be on the line at Tru. They're going to be in hotels, resorts, casinos, cruise ship galleys, corporate R&D and as baby boomers age, retirement homes, where more of a premium is put on producing a tray of identically cooked chicken breasts than on individual creativity. Garde-manger instructor Pierre Checchi says a lot of students – both career changers and those fresh out of high school – come in wanting to be the next Food Network star. He tries to disabuse them of that notion. "They all want to work in restaurants," he says. "They all want to be the next Emeril or Charlie Trotter. They don't realize that these are the exceptions." "After a few classes," says one student, "you realize that it's not as glamorous as it looks on TV. Nobody's sweating on TV." Whether their expectations are realistic or not – and instructors say they work hard to ensure that they are – culinary students are a pretty motivated bunch. "For the serious student," says Checchi, "Kendall is a great program, but if they're not serious it's a waste of time and they're wasting a lot of money." I couldn't get concrete graduation numbers from the school, but a couple students told similar stories of attrition: one remembers his class of 100 or so dwindling to 27 by graduation and another said perhaps 18 of her original 60 peers made it all the way through. Both attribute this in part to those unrealistic expectations. If people decide to go into the business, culinary school is definitely a plus," says Illona Trogub, a 21-year-old who's working on the line at the Hopleaf while she wraps up an associate's degree. "But you should work in the field for at least six months or so to get some perspective, because when you start from scratch you have no idea what you're getting into." "As a prep cook or a line cook," she continues, "culinary students aren't the best. We're definitely cocky and we think we know everything, but we don't and you learn a lot about humility when you first start out." Still, says instructor Elaine Sikorski, eventually it should all come together. "You graduate from culinary school and you might be at a disadvantage because your speed and your skills are a little slow. But in the long term, all of a sudden there's this "aha!" moment when this body of information you have stored in your brain all of a sudden seeps in and what you're doing with your hands suddenly makes sense in your mind." By 9am, Chef Sikorski has already charged through most of the day's material on the school's pristine raft Culinary Center. She's covered the difference between sea and freshwater bass, the relative merits of squid and cuttlefish, and the challenges of non-bony fish – skate, shark, dogfish, lamprey – and how to make sauce from shellfish. The 15 pupils clustered around her – second-year students just back from three-month externships – have already done two hours of prep and had breakfast. Advanced Fish and Sauce started at 6 am. "You're going to take your fish scraps, and you're going to chill them down really cold," says Sikorski, moving into a brisk run-down of the proper preparation of a mousseline, the velvety puree of fish and cream that's the foundation of today's lesson in paupiettes of sole Nantua and quenelles with watercress essence. "Chill it down really cold. And then you're going to put that metal bowl on a bowl of ice Cold, cold, cold." Before she joined Kendall's faculty eight years ago, Sikorski was the chef at Les Nomades and before that at Chicago's legendary Le Perroquet. It's safe to say she knows her French fish, but she's got just three weeks to impart that knowledge to her students.

"How fine should the grain be?" one student asks. "There should be no grain in a mousseline," says Sikorski. "Ever." At the top of the dry erase board on her left, above a hasty diagram of the best way to divvy up an asymmetrical piece of sole, is a quote from Fernand Point, the father of modern French cuisine. "Cooking," it reads, "is the accumulation of details done to perfection." Sikorski thinks that part of the perfection depends on being able to see the big picture. "Culinary school is now affording a new generation of chefs the time to think about issues like: What does it mean to use this purveyor instead of this purveyor? Is it sustainable or not? Is it organic or not?" She points out that even if a student's lucky enough to find a mentor in a working kitchen, there will barely be enough time to eat, let alone talk culinary theory. "At school we address these issues in a way that they can actually work through these issues themselves, and they can form intelligent choices. And that is a tremendous benefit. Restaurants are going to be going in that direction, where you are making more ethical and political decisions as well as financial and aesthetic decisions." The kitchen is going full tilt and quarter to 11 when Sikorski calls out, "OK, ladies and gentlemen. It's up time!" Two by two the students plate their sole and quenelles and present the results, and Sikorski grades each offering on a 20-point scale. "There's a slight over-reduction on the sauce," she pronounces of one otherwise perfect specimen of fish. "You repaired it, but you can taste the sweetness on the edge—that's the over-reduction." Another is marred by large chunks of peppercorn, a third is practically raw, a fourth is missing its crayfish garnish. Sikorski turns to the quenelles—each a pale dumpling of fish afloat on a sea of vibrant green broth. She grabs one and re-plates it to show how presentation can affect perception. She takes bits of two others in her hands and runs a finger softly over the surface of each. One is velvety smooth; the other, she points out, has a broken, mealy grain. When the grading's done she looks around. Despite all the bells and whistles of the new facility, it's suddenly clear that cooking still comes down to knives, heat, and a lot of dirty pans. "Your dish station looks like shit!" she snaps, gesturing in the direction of the sink. "Look at that! It's a mountain! Who's on sanitary?" As the students jump on the pile of dirty dishes, she walks across the hall and into the cafeteria, where a lone student from the class has been dispatched to serve the sole to his peers. "How is it?" she asks a table of students, spying the result of the past six hours of learning half-eaten on a plate. "A little under-seasoned," one replies.

"See," says Sikorski. "They've all had Fish already, so they know. |

On the fourth day of the spring quarter at Kendall College students in its culinary school were already hard at work learning to make sauce Portugaise, assemble vegetable terrines, and laminate dough for turnovers and croissants—192 layers of butter and dough for the croissants, 432 for the puff pastry. In Frank Chlumsky's Introduction to Professional Cooking, 15 entry-level students clustered in the fifth-floor auditorium and demo kitchen as he gave a brisk rundown of the differences in standard menu structures, pricing, and terminology. Two floors below, in the school's dining room kitchen, Ambarish Lulay directed his soon-to-graduate students in the production of a completely new menu for the school's Zagat-rated restaurant. Watching the sober, white-jacketed chefs in training as they navigated the hustle and bustle of the gleaming new kitchen, it was hard to believe that only a few years ago Kendall was in serious trouble. Kendall was founded in Evanston in 1934 as a liberal arts college. The culinary school wasn't added until 1985, but it soon proved to be the program that paid the bills. By 2002 more than half its students were in the culinary program, which had a first-class rep and a roster of alumni that included dozens of local notables, from "Hot Doug" Sohn to fine dining names like Eric Aubriot and Shawn McClain. But the college was suffering an identity crisis. "When I started going there as a student it was still very much a liberal arts college, with a culinary component," says food writer and culinary historian Joan Reardon, who took classes there in 1989 and served on its board in the late 90s. "But during the years I was on the board it was really a transitional period. There was this tug-of-war over whether it would continue as a four-year liberal arts college and rein in culinary a bit or go full-time into culinary school."

On the fourth day of the spring quarter at Kendall College students in its culinary school were already hard at work learning to make sauce Portugaise, assemble vegetable terrines, and laminate dough for turnovers and croissants—192 layers of butter and dough for the croissants, 432 for the puff pastry. In Frank Chlumsky's Introduction to Professional Cooking, 15 entry-level students clustered in the fifth-floor auditorium and demo kitchen as he gave a brisk rundown of the differences in standard menu structures, pricing, and terminology. Two floors below, in the school's dining room kitchen, Ambarish Lulay directed his soon-to-graduate students in the production of a completely new menu for the school's Zagat-rated restaurant. Watching the sober, white-jacketed chefs in training as they navigated the hustle and bustle of the gleaming new kitchen, it was hard to believe that only a few years ago Kendall was in serious trouble. Kendall was founded in Evanston in 1934 as a liberal arts college. The culinary school wasn't added until 1985, but it soon proved to be the program that paid the bills. By 2002 more than half its students were in the culinary program, which had a first-class rep and a roster of alumni that included dozens of local notables, from "Hot Doug" Sohn to fine dining names like Eric Aubriot and Shawn McClain. But the college was suffering an identity crisis. "When I started going there as a student it was still very much a liberal arts college, with a culinary component," says food writer and culinary historian Joan Reardon, who took classes there in 1989 and served on its board in the late 90s. "But during the years I was on the board it was really a transitional period. There was this tug-of-war over whether it would continue as a four-year liberal arts college and rein in culinary a bit or go full-time into culinary school."

Tullman's turbocharged style didn't sit well with everyone. Mike Artlip, the culinary school's associate's degree program chair, is a 29-year Kendall vet. In his role as chair of the faculty senate he acted as a buffer between the new president and the faculty and remembers being in Tullman's once on an almost daily basis. "He was very abrupt, and he probably could have been more diplomatic, but he didn't feel the need to be. He bent a few egos, but he felt like he had a job to get done."

Tullman's turbocharged style didn't sit well with everyone. Mike Artlip, the culinary school's associate's degree program chair, is a 29-year Kendall vet. In his role as chair of the faculty senate he acted as a buffer between the new president and the faculty and remembers being in Tullman's once on an almost daily basis. "He was very abrupt, and he probably could have been more diplomatic, but he didn't feel the need to be. He bent a few egos, but he felt like he had a job to get done."

Since the move to Goose Island, Kendall's profile has grown rapidly. It was ranked one of the top three culinary schools in the nation last year and college enrollment overall was up from 516 during the last quarter in Evanston to 832 this winter.

Since the move to Goose Island, Kendall's profile has grown rapidly. It was ranked one of the top three culinary schools in the nation last year and college enrollment overall was up from 516 during the last quarter in Evanston to 832 this winter.

"Roll in the egg whites and pour in the cream," she says. "Not drizzle. Pour. When it all comes together, stop the machine, take the mousseline out, and put it in a bowl on ice. Then run it through a sieve. T he goal of a mousseline is to be perfectly smooth and unctuous and to glide in your mouth and feel like pure marshmallow, without any grain to interfere with your bite."

"Roll in the egg whites and pour in the cream," she says. "Not drizzle. Pour. When it all comes together, stop the machine, take the mousseline out, and put it in a bowl on ice. Then run it through a sieve. T he goal of a mousseline is to be perfectly smooth and unctuous and to glide in your mouth and feel like pure marshmallow, without any grain to interfere with your bite."